|

|

Post by avid on Jun 15, 2009 16:42:46 GMT 4

www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/child_health/article6489311.eceFrom The Times June 13, 2009 Speed up water fluoridation for children's sake, minister urges

Sam Lister, Health Editor Andy Burnham, the new Health Secretary, yesterday urged health service managers to press ahead with the controversial fluoridation of water supplies. Speaking at the NHS Confederation annual conference, Mr Burnham, an enthusiast for fluoridation, said: “I feel we’ve been too timid at times on the public health agenda. So let’s press ahead with water fluoridation, given the clear evidence that it can improve children’s dental health.” Mr Burnham stepped down yesterday as honorary vice-president of the British Fluoridation Society after inquiries by The Times. He cited his desire not to carry a perceived conflict of interests into the fluoridation debate. Putting fluoride in water supplies, to protect teeth from decay by toughening their surface, remains a divisive issue. Opponents question the ethics of “mass medicating” the population and the efficacy of such a measure. Fluoride is added to water drunk by 5.5 million people in England — a ninth of its population — mainly in Birmingham, the West Midlands and parts of the North East. Another 500,000 people have naturally occurring fluoridated water at equivalent levels, in scattered areas mainly down the East Coast. The Government is keen to fluoridate the water supply in areas with high levels of dental decay. Successive governments and health secretaries have supported greater fluoridation, [particularly in deprived areas where nutrition is poorest and oral health discipline is weakest. Moves to introduce it more widely stalled for 30 years after local authorities lost their public health powers in 1974 and water companies were privatised. A change to the law in 2003, empowering health authorities to make water companies act, allowed the first new fluoridation scheme in Hampshire this year, despite strong opposition. Authorities in the North West, Derbyshire, Bristol and Kirklees in West Yorkshire are thought to be among those preparing to introduce similar proposals. The Scottish government decided five years ago that it did not want local authorities to have such powers and the Isle of Man dropped the idea last summer. Professor Michael Lennon, of the School of Clinical Dentistry at the University of Sheffield and chairman of the British Fluoridation Society, welcomed Mr Burnham’s support for more fluoridation. He said that an estimated 30,000 children needing dental care under general anaesthetic every year, at a cost of £1,000 each, was evidence enough of the need for strong action. “We have long been concerned about the very high level of disease in young children and the need for treatment under general anaesthetic,” he said. “It is very distressing for children and their families.” The National Pure Water Association said that there was no strong evidence to support the safety or efficacy of fluoridation. “Fluoridation proponents are therefore promoting quack medicine,” a spokesman said. “This medical intervention is currently being carried out by UK water companies without the individual consent of their customers. Water companies are doing to their customers what would attract a charge of assault and battery if a doctor did the same to a patient.”The Department of Health said there was no question of central government imposing fluoridation. “Decisions should be taken locally following consultations,” a spokesman said. He added that Mr Burnham had decided to step down from the fluoridation society with immediate effect “as he appreciates that there could be a perceived conflict of interest”. The man's crazy to advocate this! It's poison. Destroyer of the mind.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 15, 2009 23:22:21 GMT 4

Scale-Free Music of the BrainPLoS ONE

Received: January 16, 2009; Accepted: May 4, 2009; Published: June 15, 2009www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0005915;jsessionid=B224E9F8705DF99676C4925DF4910217Abstract

BackgroundThere is growing interest in the relation between the brain and music. The appealing similarity between brainwaves and the rhythms of music has motivated many scientists to seek a connection between them. A variety of transferring rules has been utilized to convert the brainwaves into music; and most of them are mainly based on spectra feature of EEG. Methodology/Principal FindingsIn this study, audibly recognizable scale-free music was deduced from individual Electroencephalogram (EEG) waveforms. The translation rules include the direct mapping from the period of an EEG waveform to the duration of a note, the logarithmic mapping of the change of average power of EEG to music intensity according to the Fechner's law, and a scale-free based mapping from the amplitude of EEG to music pitch according to the power law. To show the actual effect, we applied the deduced sonification rules to EEG segments recorded during rapid-eye movement sleep (REM) and slow-wave sleep (SWS). The resulting music is vivid and different between the two mental states; the melody during REM sleep sounds fast and lively, whereas that in SWS sleep is slow and tranquil. 60 volunteers evaluated 25 music pieces, 10 from REM, 10 from SWS and 5 from white noise (WN), 74.3% experienced a happy emotion from REM and felt boring and drowsy when listening to SWS, and the average accuracy for all the music pieces identification is 86.8%(ê = 0.800, P<0.001). We also applied the method to the EEG data from eyes closed, eyes open and epileptic EEG, and the results showed these mental states can be identified by listeners. Conclusions/SignificanceThe sonification rules may identify the mental states of the brain, which provide a real-time strategy for monitoring brain activities and are potentially useful to neurofeedback therapy. Complete article available for download at the link displayed above.

"Neurofeedback therapy", huh...I do not doubt that. What does concern me are the "other therapies" this can be used for.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 3:46:26 GMT 4

Sediment Yields Climate Record for Past Half-Million YearsOhio State University

Public Release: 15-Jun-2009researchnews.osu.edu/archive/rashid.htmCOLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers here have used sediment from the deep ocean bottom to reconstruct a record of ancient climate that dates back more than the last half-million years. The record, trapped within the top 20 meters (65.6 feet) of a 400-meter (1,312-foot) sediment core drilled in 2005 in the North Atlantic Ocean by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, gives new information about the four glacial cycles that occurred during that period. The new research was presented today at the Chapman Conference on Abrupt Climate Change at Ohio State University’s Byrd Polar Research Center. The meeting is jointly sponsored by the American Geophysical Union and the National Science Foundation. Harunur Rashid, a post-doctoral fellow at the Byrd Center, explained that experts have been trying to capture a longer climate record for this part of the ocean for nearly a half-century. “We’ve now generated a climate record from this core that has a very high temporal resolution, one that is decipherable at increments of 100 to 300 years,” he said. While climate records from ice cores can show resolutions with individual annual layers, ocean sediment cores are greatly compressed with resolutions sometimes no finer than millennia “What we have is unprecedented among marine records.” Dating methods such as carbon-14 are useless beyond 30,000 years or so, he said, so Rashid and his colleagues used the ratio of the isotopes oxygen-16 to oxygen-18 as a proxy for temperature in the records. The isotopes were stored in the remains of tiny sea creatures that fell to the ocean bottom over time. When the researchers compared their record of past climate from the North Atlantic to a similar record taken from an ice core drilled from Dome C in Antarctica, they found it was remarkably similar. “You can’t miss the similarity between the two records, one from the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean and the other from Antarctica,” he said. “The record is virtually the same regardless of the location.” Surprisingly, Rashid’s team was also able to score another first with their analysis of this sediment core – a record of the temperature at the sea surface in the North Atlantic. They drew on knowledge readily known to chemists that the amount of magnesium trapped in calcite crystals can indicate the temperatures at which the crystals formed. The more magnesium present, the warmer the waters were when the tiny organisms were alive. They applied this analysis to the remains of the benthic organisms in the cores and were able to develop a record of warming and cooling of the sea surface in the North Atlantic for the last half-million years. Having this information will be useful as scientists try to understand how quickly the major ocean currents shifted as glacial cycles came and went, Rashid said. The researchers were also able to gauge the extent of the ancient Laurentide Ice Sheet that covered much of North America during the last 130,000 years. As that ice sheet calved off icebergs into the Atlantic, Rashid said that the “dirty underbelly” of those icebergs carried gravel out into the ocean. As the bergs melted, the debris fell to the bottom and of the ocean floor. The more debris present, the more icebergs had been released to carry it, meaning that the ice sheet itself had to have been larger. “Based on this, we’ve determined that the Laurentide Ice Sheet was probably largest during the last glacial cycle than it was during any of the three previous cycles,” he said. During the last glacial cycle, the Laurentide Ice Sheet was more than a kilometer (.6 miles) thick and extended to several miles north of Ohio State. Along with Rashid, researchers from the University of South Florida, the University of Bremen in Germany, and the Laboratorio Nacional de Energia e Geologia in Portugal contributed to the work.

Contact: Harunur Rashid, (614) 292-5040; rashid.29@osu.edu

Written by: Earle Holland, (614) 292-8384; holland.8@osu.edu

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 4:06:14 GMT 4

Meteorite grains divulge Earth's cosmic rootsEurekAlert

Public Release: 15-Jun-2009www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2009-06/uoc-mgd061509.phpThis is University of Chicago postdoctoral scientist Philipp Heck with a sample of the Allende meteorite. The dark portions of the meteorite contain dust grains that formed before the birth of the solar system. The Allenda meteorite is of the same type as the Murchison meteorite, the subject of Heck’s Astrophysical Journal study. Credit: Dan DryThe interstellar stuff that became incorporated into the planets and life on Earth has younger cosmic roots than theories predict, according to the University of Chicago postdoctoral scholar Philipp Heck and his international team of colleagues. Heck and his colleagues examined 22 interstellar grains from the Murchison meteorite for their analysis. Dying sun-like stars flung the Murchison grains into space more than 4.5 billion years ago, before the birth of the solar system. Scientists know the grains formed outside the solar system because of their exotic composition."The concentration of neon, produced during cosmic-ray irradiation, allows us to determine the time a grain has spent in interstellar space," Heck said. His team determined that 17 of the grains spent somewhere between three million and 200 million years in interstellar space, far less than the theoretical estimates of approximately 500 million years. Only three grains met interstellar duration expectations (two grains yielded no reliable age). "The knowledge of this lifetime is essential for an improved understanding of interstellar processes, and to better contain the timing of formation processes of the solar system," Heck said. A period of intense star formation that preceded the sun's birth may have produced large quantities of dust, thus accounting for the timing discrepancy, according to the research team.Citation: "Interstellar Residence Times of Presolar Dust Grains from the Murchison Carbonaceous Meteorite," Astrophysical Journal, June 20, 2009, Vol. 698, Issue 12, pages 1155-1164

Authors: Philipp R. Heck, University of Chicago Department of Geophysical Sciences and Chicago Center for Cosmochemistry

Frank Gyngard, Laboratory for Space Sciences and Physics Department, Washington University, St. Louis

Ulrich Ott, Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, Germany

Matthias M.M. Meier, Institute of Isotope Geology and Mineral Resources, Zurich, Switzerland

Janaína N. Ávila, Research School of Earth Sciences and Planetary Science Institute, Australian National University, Canberra

Sachiko Amari, Laboratory for Space Sciences and Physics Department, Washington University, St. Louis

Ernest K. Zinner, Laboratory for Space Sciences and Physics Department, Washington University, St. Louis

Roy S. Lewis, Enrico Fermi Institute and the Chicago Center for Cosmochemistry, University of Chicago

Heinrich Baur, Institute of Isotope Geology and Mineral Resources, Zurich, Switzerland

Rainer Wieler, Institute of Isotope Geology and Mineral Resources, Zurich, Switzerland

Funding sources: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Swiss National Science Foundation, the Australian National University, and the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 4:17:07 GMT 4

Caltech scientists use high-pressure 'alchemy' to create nonexpanding metalsEurekAlert

Public Release: 15-Jun-2009www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2009-06/ciot-csu061509.phpPasadena, CA—By squeezing a typical metal alloy at pressures hundreds of thousands of times greater than normal atmospheric pressure, scientists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have created a material that does not expand when heated, as does nearly every normal metal, and acts like a metal with an entirely different chemical composition. The discovery, described in a paper in Physical Review Letters (PRL), offers insight into the exotic behavior of materials existing at high pressures—which represent some 90 percent of the matter in our solar system. Zero-expanding metal alloys were discovered in 1896 by Swiss physicist Charles Édouard Guillaume, who worked at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in France. While attempting to develop an inexpensive international standard for the meter, the metric unit of length, Guillaume hit upon an inexpensive iron-nickel alloy that expands very little when heated. He dubbed the material an "Invar" alloy—because the metals are "invariant" when heated, such that the length of a piece of Invar metal does not change as its temperature is increased, as do normal metals. Since Guillaume's discovery—which, in 1920, earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics (besting Albert Einstein, who was awarded the prize in 1921)—other nonexpanding alloys have been identified. It has long been known that Invar behavior is caused by unusual changes in the magnetic properties of the alloys that somehow cancel out the thermal expansion of the material. (Normally, heat increases the vibrations of the atoms that make up a material, and the atoms prefer to move apart a little, causing expansion.) "Recent computer simulations indicate that electrons in Invar alloys take on a special energy configuration," says Caltech graduate student Michael Winterrose, the first author of the PRL paper. "This energy state is at the borderline between two types of magnetic behavior, and is very sensitive to the precise ratio of elements that make up the alloy. If you move away from the Invar chemical composition by only a couple of percent, the energy configuration will disappear," he says. Because of their unresponsiveness to temperature change, Invar alloys have been used in devices ranging from watches, toasters, light bulbs, and engine parts to computer and television screens, satellites, lasers, and scientific instruments. "In our day-to-day lives, we are surrounded by items that make essential use of Invar alloys," Winterrose says. The Caltech scientists did not set out to study Invar behavior—and, in fact, were hoping to avoid it. "We intentionally picked chemical compositions that do not show Invar behavior because I thought it would confuse our interpretations," says Brent Fultz, a professor of materials science and applied physics at Caltech, and a coauthor of the PRL paper. Instead, Winterrose, Fultz, and their colleagues were examining the effect of pressure on the alloy of palladium (Pd) and iron (Fe) called Pd3Fe, where three of every four atoms are palladium, and one is an iron atom. (In the similarly named but chemically distinct PdFe3—which is a traditional Invar alloy—three of every four atoms are iron, and one is palladium). "The Fe and Pd atoms [in the alloy] have very different sizes, and we expected to see some interesting effects from this size difference when we put Pd3Fe under pressure and measured its volume," Winterrose explains. To test this, the scientists squeezed a small sample of the material between two diamond anvils, generating pressures inside the sample that were 326,000 times greater than standard atmospheric pressure. "Our initial results from these studies showed that the alloy stiffened under pressure, but far more than we expected," he says. To figure out the cause, the scientists simulated the quantum mechanical behavior of the electrons in the alloy under pressure. "The simulations showed that under pressure, the electrons found the special energy levels between strong and weak magnetism that are associated with normal Invar behavior. Up to this point we had been quite unaware of the possibility for Invar behavior in our material," Winterrose says. Subsequent experiments at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago and the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York confirmed that the intense pressure had indeed suppressed thermal expansion in Pd3Fe, much like tuning the chemical composition. The scientists had performed a kind of high-pressure "alchemy" on the alloy, where pressure makes the electrons act as if they are around atoms of a different chemical element, Winterrose says. The research helps unify our understanding of Invar behavior, which is one of the oldest and most-studied unresolved problems in materials research. In addition, using pressure to force electrons into new states can point to directions in materials chemistry where new properties can be found, at least for magnetism. "Today, materials physics has some excellent computational tools for predicting the structure and properties of materials, although there are suspicions about how well they work for magnetic materials," says Fultz. "It is satisfying that these computational tools worked so well for showing how pressure changed the material into an Invar alloy. Invar behavior is pretty subtle, requiring a very special condition for the electrons in the metal that is usually tuned by precise control of chemical composition. Pressure can make the electrons behave as if they are in a material of different chemical composition, so I really like Mike's use of the word 'alchemy'." The paper, "Pressure-Induced Invar Behavior in Pd3Fe," was published in the June 12 issue of PRL. In addition to Winterrose and Fultz, the coauthors are Matthew S. Lucas, Alan F. Yue, Itzhak Halevy, Lisa Mauger, and Jorge Munoz (from Caltech); Jingzhu Hu, from the University of Chicago; and Michael Lerche, from the Carnegie Institution for Science.

The work was supported by the Carnegie–Department of Energy (DOE) Alliance Center, funded by the DOE through the Stewardship Sciences Academic Alliance of the National Nuclear Security Administration, and by the DOE's Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences; by the National Science Foundation and its Consortium for Materials Properties Research in Earth Sciences (COMPRES); and by the W. M. Keck Foundation.

Visit the Caltech Media Relations website at media.caltech.edu.I like the use of the term "alchemy", too. Especially since Argonne, Brookhaven, Carnegie and the DOE were involved in the research...oh, and CalTech, too.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 4:28:41 GMT 4

New study closes in on geologic history of Earth's deep interiorUC Davis team calculates distribution of iron isotopes in Earth's mantle 4.5 billion years ago, opening door to new studies of planet's geologic historyEurekAlert

Public Release: 15-Jun-2009www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2009-06/uoc--nsc061509.phpThis schematic of Earth’s crust and mantle shows the results of a new study that found that extreme pressures would have concentrated iron’s heavier isotopes near the bottom of the mantle as it crystallized from an ocean of magma to its solid form 4.5 billion years ago. Credit: Louise Kellogg, modified by James Rustad & Qing-zhu Yin/UC DavisBy using a super-computer to virtually squeeze and heat iron-bearing minerals under conditions that would have existed when the Earth crystallized from an ocean of magma to its solid form 4.5 billion years ago, two UC Davis geochemists have produced the first picture of how different isotopes of iron were initially distributed in the solid Earth. The discovery could usher in a wave of investigations into the evolution of Earth's mantle, a layer of material about 1,800 miles deep that extends from just beneath the planet's thin crust to its metallic core. "Now that we have some idea of how these isotopes of iron were originally distributed on Earth," said study senior author James Rustad, a Chancellor's fellow and professor of geology, "we should be able to use the isotopes to trace the inner workings of Earth's engine." A paper describing the study by Rustad and co-author Qing-zhu Yin, an associate professor of geology, was posted online by the journal Nature Geoscience on Sunday, June 14, in advance of print publication in July. Sandwiched between Earth's crust and core, the vast mantle accounts for about 85 percent of the planet's volume. On a human time scale, this immense portion of our orb appears to be solid. But over millions of years, heat from the molten core and the mantle's own radioactive decay cause it to slowly churn, like thick soup over a low flame. This circulation is the driving force behind the surface motion of tectonic plates, which builds mountains and causes earthquakes. One source of information providing insight into the physics of this viscous mass are the four stable forms, or isotopes, of iron that can be found in rocks that have risen to Earth's surface at mid-ocean ridges where seafloor spreading is occurring, and at hotspots like Hawaii's volcanoes that poke up through the Earth's crust. Geologists suspect that some of this material originates at the boundary between the mantle and the core some 1,800 miles beneath the surface. "Geologists use isotopes to track physico-chemical processes in nature the way biologists use DNA to track the evolution of life," Yin said. Because the composition of iron isotopes in rocks will vary depending on the pressure and temperature conditions under which a rock was created, Yin said, in principle, geologists could use iron isotopes in rocks collected at hot spots around the world to track the mantle's geologic history. But in order to do so, they would first need to know how the isotopes were originally distributed in Earth's primordial magma ocean when it cooled down and hardened. As a team, Yin and Rustad were the ideal partners to solve this riddle. Yin and his laboratory are leaders in the field of using advanced mass spectrometric analytical techniques to produce accurate measurements of the subtle variations in isotopic composition of minerals. Rustad is renowned for his expertise in using large computer clusters to run high-level quantum mechanical calculations to determine the properties of minerals. The challenge the pair faced was to determine how the competing effects of extreme pressure and temperature deep in Earth's interior would have affected the minerals in the lower mantle, the zone that stretches from about 400 miles beneath the planet's crust to the core-mantle boundary. Temperatures up to 4,500 degrees Kelvin in the region reduce the isotopic differences between minerals to a miniscule level, while crushing pressures tend to alter the basic form of the iron atom itself, a phenomenon known as electronic spin transition. Using Rustad's powerful 144-processor computer, the two calculated the iron isotope composition of two minerals under a range of temperatures, pressures and different electronic spin states that are now known to occur in the lower mantle. The two minerals, ferroperovskite and ferropericlase, contain virtually all of the iron that occurs in this deep portion of the Earth. These calculations were so complex that each series Rustad and Yin ran through the computer required a month to complete. In the end, the calculations showed that extreme pressures would have concentrated iron's heavier isotopes near the bottom of the crystallizing mantle. It will be a eureka moment when these theoretical predictions are verified one day in geological samples that have been generated from the lower mantle, Yin said. But the logical next step for him and Rustad to take, he said, is to document the variation of iron isotopes in pure chemicals subjected to temperatures and pressures in the laboratory that are equivalent to those found at the core-mantle boundary. This can be achieved using lasers and a tool called a diamond anvil. "Much more fun work lies ahead," he said. "And that's exciting." The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Basic Energy Sciences, and by a NASA Cosmochemistry grant and a NASA Origins of Solar Systems grant.

An abstract of the paper "Iron isotope fractionation in the Earth's lower mantle" can be found at www.nature.com/ngeo/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/ngeo546.html.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 4:43:32 GMT 4

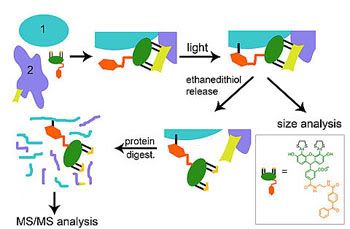

TRAPping proteins that work together inside living cellsNew way to probe for proteins working together reveals never-before-seen details of RNA polymerase in bacteriaPacific Northwest National Laboratory

Release date: June 15, 2009www.pnl.gov/news/release.asp?id=379TRAP (in green, orange and yellow) binds to a tag on known protein (#2). Light crosslinks TRAP's benzophenone to mystery protein (#1). Subsequent biochemical analysis reveals clues to unknown protein (#1). (Original high-resolution image.)RICHLAND, Wash. – DNA might be the blueprint for living things, but proteins are the builders. Researchers trying to understand how and which proteins work together have developed a new crosslinking tool that is small and unobtrusive enough to use in live cells. Using the new tool, the scientists have discovered new details about a well-studied complex of proteins known as RNA polymerase. The results suggest the method might uncover collaborations between proteins that are too brief for other techniques to pinpoint. "Conventional methods used to find interacting proteins have limitations that we are trying to circumvent," said biochemist Uljana Mayer of the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. "They also create conditions that are different from those inside cells, so you can't find all the interactions that proteins would normally engage in." Proteins are the workhorses in an organism's cells. Whole fields of research are dedicated to teasing out which proteins work together to make cells function. For example, drug researchers seek chemicals that disrupt or otherwise change how proteins interact to combat diseases; environmental scientists need to understand how proteins collaborate in ecosystems to make them thrive or fail. To learn about protein networks, scientists start with a familiar one and use it as bait to find others that work alongside it. To pin down the collaborators, researchers make physical connections between old and new proteins with chemicals called crosslinkers. The sticky crosslinkers will only connect proteins close enough to work together, the thinking goes. But most crosslinkers are too large to squeeze into living cells, are harmful to cells, or link proteins that are neighbors but not coworkers. To address these issues, Mayer and her PNNL colleagues developed a crosslinking method that uses small crosslinkers whose stickiness can be carefully controlled. To find coworkers of a protein of interest, Mayer and her colleagues build a tiny molecule called a tag into the initial protein. They then add a small molecule called TRAP to the living cell, which finds and fits into the tag like two pieces in a puzzle. TRAP waves around, bumping into nearby proteins. The scientists control TRAP with a flash of light, causing it to stick to coworkers it bumps into. The researchers then identify the new "TRAPped" proteins in subsequent analyses. To demonstrate how well this method works, Mayer and colleagues tested it out on RNA polymerase, a well-studied machine in cells. The polymerase is made up of many proteins that cooperate to translate DNA. One of the polymerase proteins has a tail that is known to touch the DNA and some helper proteins just before the polymerase starts translating. No one knew if this tail -- also known as the C-terminus of the alpha subunit -- touches anything else in the core of the RNA polymerase complex. The team engineered a tag in the C-terminus and cultured bacteria with the tagged RNA polymerase. After adding TRAP to the cells and giving it time to find the C-terminus tag, the team shined a light on the cultures. The team then identified the proteins marked with TRAP using instruments in EMSL, DOE's Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory on the PNNL campus. They found that the tagged protein, as expected, interacts with many other proteins, for example previously identified helper proteins, so-called transcription factors. But they also found it on another core protein called the beta subunit, suggesting the tail of the alpha subunit makes contact with the beta subunit as it plugs along. This interaction had never been seen before. "No one knows what the polymerase looks like when it is running," said Uljana Mayer. "Here we see the C-terminus swings back to grab the beta subunit once the polymerase starts working." The team report their results June 15 in the journal ChemBioChem. The tag in their unique method is made up of a "tetracysteine motif" -- two pairs of the amino acid cysteine separated by two other amino acids that doesn't interfere with the normal function of the protein of interest. TRAP includes a small "biarsenical" probe, which fluoresces so the team can find the proteins to which it has become attached. TRAP can also be easily unlinked from the tag with a simple biochemical treatment, allowing researchers to piece out the coworker from their original protein of interest. The team also tested the method on other proteins, such as those found in young muscle cells. Mayer said they will use the method in the future to understand how environmental conditions affect how proteins work together in large networks. Reference: P. Yan, T. Wang, G.J. Newton, T.V. Knyushko, Y. Xiong, D. J. Bigelow, T.C. Squier, and M.U. Mayer, A Targeted Releasable Affinity Probe (TRAP) for In Vivo Photo-Crosslinking, ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 1507 - 1518, DOI 10.1002/cbic.200900029.

This work was supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science's Office of Biological and Environmental Research.

EMSL, the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, is a national scientific user facility sponsored by the Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research program that is located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. EMSL offers an open, collaborative environment for scientific discovery to researchers around the world. EMSL's technical experts and suite of custom and advanced instruments are unmatched. Its integrated computational and experimental capabilities enable researchers to realize fundamental scientific insights and create new technologies.

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is a Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory where interdisciplinary teams advance science and technology and deliver solutions to America's most intractable problems in energy, national security and the environment. PNNL employs 4,250 staff, has a $918 million annual budget, and has been managed by Ohio-based Battelle since the lab's inception in 1965.

|

|

|

|

Post by nodstar on Jun 16, 2009 4:52:44 GMT 4

Sally Anne a Pm awaits

Nod

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 5:20:24 GMT 4

Russia hosts first BRIC summit, India-Pakistan meetNewsDaily

Posted 2009/06/15 at 8:18 pm EDTwww.newsdaily.com/stories/tre55f02f-us-summit/YEKATERINBURG, Russia — The world's biggest emerging market powers will seek to craft a united front on repairing the global financial system when they meet for the first formal BRIC summit on Tuesday. Before the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India and China meet, a summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) of Central Asian powers will also underline the growing international stature of China and Russia. The four BRIC nations -- which account for 15 percent of the $60.7 trillion global economy -- will focus on ways to reshape the financial system after the economic crisis. But immediate agreement on practical steps among the members of this loose and untested bloc appears most unlikely. "These four countries are all quite influential in international economic development, and I think if in the meeting they raise some proposals and initiatives, that would be fair and reasonable," said Wu Hailong, a senior Chinese Foreign Ministry official.

"Especially, some countries have proposed establishing a super-sovereign currency, and I think their impetus is ensuring the security of each country's foreign currency reserves."

Chinese and Russian officials have in recent days played down talk of a discussion on a new supranational reserve currency to reduce dependency on the U.S. dollar.The BRIC term was coined by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O'Neill in 2001 to describe the growing power of emerging market economies. Tuesday's summit in the Russian Urals city of Yekaterinburg marks a step toward cohesion as a group. INDIA, PAKISTANA one-on-one meeting between Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari is planned on the sidelines of the SCO summit and could help break the ice between the two nuclear-armed powers.The SCO summit is likely to produce general pledges to work together more closely for regional development and security. Iran, while only an observer member of the SCO, has again stolen much of the attention at the SCO summit. Doubt hangs over whether President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad will attend the SCO summit this year, defying street demonstrations that have decried his re-election last week as rigged. He did not arrive on Monday, when the SCO opened its two-day summit, but he may arrive on Tuesday. As part of proposals to rebuild the financial system, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev has made proposals on giving a greater role to the International Monetary Fund's Special Drawing Rights that echo ideas from Chinese central bank chief Zhou Xiaochuan.

Russia said it would reduce the share of U.S. Treasuries in its $400 billion reserves and buy IMF bonds. China, Russia and Brazil have pledged to help capitalize the IMF as they seek more influence at the fund."China and Russia share some agreement on general ideas about dealing with the financial crisis and regional issues, otherwise the BRIC summit wouldn't be happening at all," said Zhao Huasheng, an expert the two countries' relations at Fudan University in Shanghai. "But translating those concepts into practice is difficult, especially when there are so many other diverse countries also present," said Zhao.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 5:40:16 GMT 4

Autism and ToxinsHuffington Post

Jay Gordon, MD (Nationally renowned pediatrician on the faculty of UCLA School of Medicine)

Posted: June 15, 2009 03:11 AMwww.huffingtonpost.com/jay-gordon/autism-and-toxins_b_215461.htmlDr. Harvey Karp has just written an excellent blog beginning to discuss the role environmental toxins play in causing autism. I agree that the huge rise in autism is real, and not just related to better diagnosis or reclassification of mental illness. Autism is most likely caused by a genetic predisposition and an environmental "trigger." Studies showing that vaccines and their many constituents do not contribute to this problem are flawed, filled with specious reasoning and, for the most part funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Even articles in reputable medical journals are often written by doctors with an economic interest in continuing the vaccination program's status quo. This does not invalidate all of these studies but it certainly makes them suspect and a poor foundation for an argument excluding vaccines from the list of environmental influences on the increase in autism in America and elsewhere.The facile dismissal of those of us calling for safer vaccinations and scrutiny of the current vaccine schedule is not scientifically based and polarizes the discussion. Perhaps most importantly, this dismissal is insulting to the thousands of parents and families who aver that their children have been harmed by vaccines. There are extremists choosing to ignore the facts in all vaccine/autism camps. I am not one of them. Asking that cars be manufactured with more attention to safety and that driving is best when done safely does not make one "anti-car" or anti-driving. Asking for safer vaccinations and more judicious use of those we have does not make me or anyone else "anti-vaccine."The studies Dr. Karp cites show pretty much the opposite of what he's claiming they do. The opposite. The Danish Study's data are misused by all and interpreted to suit one's needs. The Japanese study also shows a connection between the MMR split into three components and autism. Mainstream medical journals rarely will publish editorial comment impugning the quality or integrity of vaccines because they are dependent upon the good graces of the pharmaceutical industry for their publishing dollars. Seeking out reputable commentators is difficult because the extremists on both sides of this debate exaggerate their claims and speak louder and more unpleasantly as if this helps to make their points.In April of 2009, the "Journal of the American Medical Association" spoke to the conflict of interest and possible corruption as the journals, the AMA, the AAP and other medical associations rely on money from the manufacturers of vaccines and other drugs. I have been in practice thirty years and watched thousands of children get shots, not get shots, develop autism or remain developmentally "neurotypical." I have no proof that vaccines cause autism and would be very excited to have my large group of extremely healthy mostly unvaccinated children studied someday. It would be disingenuous to imply that non-vaccination might not lead to an increased incidence in vaccine-preventable illness. It would be equally disingenuous to state that this possibility poses a great threat to America's children. The risks of vaccinating the way we do now exceeds the benefits of this vaccine program. "Scientists" who suggest that experienced doctors ignore their eyes and ears are wrong. Detractors who say that we should ignore parents who are certain that vaccines caused their children's autism are wrong and often quite mean-spirited.Dr. Karp, if you are going to talk and blog about kitchen cleaners, furniture polish, pesticides and other toxins, how can you possibly ignore the 30-40 injections of potentially risky material we give children in their first 24 months of life? There is absolutely no proof that these shots are as safe the makers say they are and certainly no proof that new combinations of vaccines and hastily created shots are safe enough for our children. Certain childhood illnesses are far less common than before we had vaccines to decrease their numbers. When numbers drop so low for certain illnesses, we have to cast a strong critical eye on the possible side effects of a vaccine. This loving, reasonable principle can initially be applied by an individual parent to an individual child and family. We certainly have to add public health into this complicated calculus of risk versus reward. It remains very possible that changing the way we manufacture vaccines and being more selective in our use of them may have huge public health benefits. It would be unscientific and immoral to ignore these more difficult possibilities in favor of the easier answers in Dr. Karp's post. We can save more children if just think harder.Giving children the chicken pox vaccine may lead to huge shingles problems in adults. Autism is triggered by many environmental, infectious and other causes. Vaccines are one of these triggers. Believe the parents!Related: Dr. Harvey Karp Cracking the Autism Riddle: "Vaccine Theory" Fades as a New Idea Emerges

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 6:17:07 GMT 4

Whistling Past the Economic Graveyard: The Audacity of Misplaced HopeHuffington Post

Arianna Huffington

Posted: June 15, 2009 04:26 PMwww.huffingtonpost.com/arianna-huffington/whistling-past-the-econom_b_215672.htmlIs it possible to have too much hope? To be too optimistic? Yes, if that hope keeps you from facing -- and dealing with -- unpleasant realities. That seems to be what's happening regarding the financial institutions responsible for the economic meltdown. Let's start with the banks' toxic assets. When Tim Geithner unveiled the Public Private Investment Program, he said that dealing with these assets was a "core" part of solving the financial crisis.But the banks would much rather keep pretending that their toxic assets are not that toxic, and worth much more than they really are -- a risky charade the relaxed mark-to-market rules allow them to continue to pull off. So, last week, the PPIP program was apparently scrapped. Does this mean that the toxic assets are no longer a "core" part of the problem? Or that hoping they're no longer part of the problem will somehow make them no longer part of the problem? [Note: They'll just handle the toxic assets at a Level 5 HAZMAT facility - right next to the "biochemical weapons" development labs.]"Hope sustains life, but misplaced hope prolongs recessions." So says Jim Grant, publisher of the Grant's Interest Rate Observer newsletter, whom I interviewed last week on Squawk Box. Because of misplaced hope, Grant says, business people, homeowners -- and administrations -- often refuse to admit the truth and take the painful steps necessary to turn things around. [Note: We have hope. That hasn't changed. The yahoos (aka goobers) running this scam are "hopelessly lost in a cloud of their own chemtrail seeding".]On Wednesday, President Obama will lay out the details of his administration's plan to remake the financial regulatory system. Geithner and Larry Summers offered a sneak peak at the plan in an op-ed in today's Washington Post, proclaiming, "we must begin today to build the foundation for a stronger and safer system." Among the proposals: "raising capital and liquidity requirements for all institutions"; "consolidated supervision by the Federal Reserve"; "robust reporting requirements on the issuers of asset-backed securities" including "strong oversight of 'over the counter' derivatives"; and providing "a stronger framework for consumer and investor protection across the board." [Note: I wouldn't let the Federal "Me"serve Bank supervise the cleaning of toilets...but that's my personal opinion.  ]The devil, of course, will be in the details. And on how much muscle Obama puts behind pushing these measures through and ensuring they become law without being watered down. Especially at a time when the latest stock market bubble has undermined the urgent push for reform, which seems to have given way to a push to move on to other things and leave that little financial kerfuffle behind us.[Note: The stock market "bubble" has been caused by the release of toxic fumes from the aforementioned toxic assets. Given that the "bankie babies" along with their "beanie baby counterparts" on the Hill, were instrumental in the formation of this "gas configuration", it wouldn't surprise me if the "bubble bust" that's due raises the bar on METHANE disbursement in the atmosphere.] ]The devil, of course, will be in the details. And on how much muscle Obama puts behind pushing these measures through and ensuring they become law without being watered down. Especially at a time when the latest stock market bubble has undermined the urgent push for reform, which seems to have given way to a push to move on to other things and leave that little financial kerfuffle behind us.[Note: The stock market "bubble" has been caused by the release of toxic fumes from the aforementioned toxic assets. Given that the "bankie babies" along with their "beanie baby counterparts" on the Hill, were instrumental in the formation of this "gas configuration", it wouldn't surprise me if the "bubble bust" that's due raises the bar on METHANE disbursement in the atmosphere.]And investors seem anxious to do the same. Witness the "fierce rally" in the collateralized loan obligation market. CLOs are made up of sliced and diced assets (including high-risk and junk loans) -- and are kissing cousins to the collateralized-debt obligations (i.e. crap) at the heart of the financial meltdown. But according to analysts at Morgan Stanley * there has recently been a "remarkable change" in investor sentiment towards these securities, including an "exuberance" for the lowest grade junk being sold. [/li][li][/b][/color] In other words, we are right back to risky business as usual. No harm, no foul. Let's get back to the fun we were having before this whole worldwide economic collapse thing started happening. [Note: Yeah - fun...  ] ]It puts a whole other spin on the audacity of hope. Too many in Washington -- and in the media continue to take the well-being of Wall Street as the proper gauge for the well-being of the rest of America. Yes, the Dow is up 33 percent since March. But another 345,000 jobs were lost in May, raising the number of the unemployed to 14.5 million, and the unemployment rate to 9.4 percent. Since the start of the recession in December 2007, unemployment has almost doubled. [Note: Goober Media Propaganda Tactics. What a bunch of "dipsticks" - and that's MY gauge. You goobers are at least a quart short...]What's more, as this chart shows, over the past two decades, the top one percent of Americans has done very well in terms of wage growth. Things have not been nearly as good for everybody else. [Note: That pie chart was deleted from the "PowerPoint Presentation" because they couldn't find a sizing wedge small enough to represent the other 99% (that would be us).]Are the reforms going to be sufficiently fundamental to avoid a repeat of the boom and bust cycles, in which only a select few enjoy the boom and everybody else pays for the bust? [Note: In order for the reforms to be "sufficiently fundamental" we need to do some "fundamental purging at the Hill of Beans".]

The bottom line is: We don't need the goobers - they need us. That's reality. You need to wake up and pay attention.

|

|

|

|

Post by fr33ksh0w2012 on Jun 16, 2009 8:52:10 GMT 4

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 16:34:06 GMT 4

Hiya fr33ksh0w2012!

You have a PM!

Peace and Joy

Always

Sally Anne

|

|

|

|

Post by Eagles Disobey on Jun 16, 2009 18:26:13 GMT 4

HAPPY 18TH. ANNIVERSARY, EAGLES, FROM THE WHOLE TEAM THAT LOVES YOU BOTH!

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Jun 16, 2009 20:00:58 GMT 4

Australian Forests Best at Locking Up CarbonAnna Salleh, ABC Science Online

Discovery News

June 16, 2009dsc.discovery.com/news/2009/06/16/australia-forest-carbon.html

Getty ImagesMountain ash forests in Australia are the best in the world at locking up carbon, a new study has found. And one of the authors said climate change negotiations should give more attention to protecting forests like these. Environmental scientist, Brendan Mackey of the Australian National University and colleagues report their findings in today's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. "Currently everyone is focussed on how to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation in developing countries," said Mackey. "But what this points to is that we can't forget about emissions from natural forests in economically developed countries like Australia." In the first study of its kind, Mackey and colleagues compared the amount of carbon per unit area locked up in 132 forests around the world. Forests ranged from the Amazon in the tropics to temperate moist forests, such as stands of mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) in Victoria's Central Highlands. They calculated the total biomass locked up in living and dead plant material and the soil of each forest. Mackey and colleagues found the highest amount of carbon was contained in a forest located in Victoria's Central Highlands, which held 1900 tons of carbon per hectare. This most "carbon-dense" forest was a stand of unlogged mountain ash over 100 years old. Mountain ash live for at least 350 years, said Mackey. He said similar but lower carbon densities were found for other temperature moist forests in New Zealand, Chile and the Pacific coast of North America. By comparison, the average tropical forest had somewhere between 200 and 500 tons of carbon per hectare, said Mackey. "The common understanding is that tropical forests store the most carbon because they're the most biologically productive and have the most plant growth," said Mackey. But, he said, researchers have missed the fact that nearly half of the carbon locked up in temperate forests like the mountain ash, is in fallen trees and other dead plant material. In tropical forests, dead plant material is rapidly decomposed and carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere through respiration. By contrast, moist temperate forests are warm enough to encourage good growth rates, dead plant material decays much more slowly and carbon-rich dead biomass lasts much longer. Mackey said the findings reinforce the role of forests in storing carbon and in mitigating climate change. He said the research especially underscores the importance of protecting carbon-dense forests in developed countries. Under the Kyoto Protocol, countries are not required to account for carbon lost through degradation and deforestation of their native forests, said Mackey. He said, the upcoming Copenhagen climate change negotiations should rectify this. The forest industry argues logging old growth forests is important to reduce the risk of bushfire, which releases CO 2 emissions. "If we lock up and leave these forests, what we're actually doing is increasing the risk that these forests will burn down," Allan Hansard, CEO of the National Association of Forest Industries, told ABC Radio today. [Note: Please spare me the "dire warnings". The only thing in danger is your profit margins. Look at the science. In fact, look at the global climate picture. If you burn these forests, you increase the amount of CO2 released into the atmosphere WHICH WILL INCREASE THE DANGERS OF FOREST FIRES by the continued destabilization of many intricate ecological and atmospheric balances.]"This is important from a climate change perspective because if you actually have a look at the amount of emissions from these fires it's actually quite substantial." But Mackey said most of the carbon is in the woody biomass and soil, which is not burnt in fires. And he said logging actually increases the risk of fire by opening up the forest, increasing the amount of fuel on its floor, and drying the forest out. Mackey said another common misunderstanding is that younger growing forests sequester more carbon than mature forests. He said while growing forests have a greater rate of carbon uptake, it's more important to look at the total amount of carbon stored in a forest. Since carbon is emitted much more rapidly than it is sequestered, Mackey said the best way to sequester carbon forests is to protect existing old forests. "If you take one of these mature [mountain ash] forests with 1900 tons of carbon in it and trash it ... it's going to take hundreds of years to grow back that amount of carbon."

|

|