|

|

Post by nodstar on Sept 28, 2009 4:11:44 GMT 4

Hi Everyone .. Here's the new SCIENCE NEWS thread  |

|

|

|

Post by nodstar on Sept 28, 2009 8:21:17 GMT 4

Mountains may be cradles of evolution[/size] Natural News www.nature.com/news/2009/090925/full/news.2009.952.html?s=news_rss2009-09-27  Growing mountains may give rise to new species — and not simply provide a refuge to species whose traditional habitats have been lost, US scientists suggest. "The major times of [species] diversification directly coincide with times of large tectonic events," says Catherine Badgley, a palaeontologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who presented the findings this week at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Bristol, UK. Mountainous regions are known to harbour higher levels of species richness than other areas. The reason, ecologists argue, is because mountains offer many different habitats in a relatively small geographical area. For example, whereas ten square kilometres of plains offer just one habitat, the same area of mountain landscape can provide sloping meadows, peaks and cliffs, all with different temperatures, rainfall and vegetation. The long-standing view among ecologists has been that mountainous areas act as refuges for species that have been driven out of their normal habitat by difficult environmental conditions. A typical example could be a species dwelling in plains near the base of mountains — a change in conditions on the plains might mean that mountain areas begin to suit the needs of the species better, causing it to migrate. "Mountains have always been considered the places for species to make their last stands because they offer such diverse terrain," notes Russell Graham, a palaeoecologist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. Curious about the mechanisms responsible for making mountains so rich in diversity, Badgley and her collaborator John Finarelli, also at the University of Michigan, studied mountain and lowland speciation rates and species richness using the fossil record of the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains in North America. The fossils they inspected date to the Miocene period, which began around 23 million years ago and ended about 5 million years ago. They found that there were bursts of speciation that took place only in the mountains during times of tectonic activity. During all other times, they discovered that speciation rates in the two regions were moderate and similar. Isolating incident Although the highly varied terrain of mountains helps to explain why so many different species can live there, the question of where the species richness actually comes from has never been addressed, explains Badgely. She and Finarelli now propose that as mountains are lifted up by the tectonic processes of the Earth's crust, mountain-dwelling species become isolated from other members of the same species living at lower altitudes. This isolation ultimately leads to the two groups breaking apart to form individual species. "We had never thought of mountains as the birthplaces of species before," says Graham. However, mountains might not be the only areas where speciation is taking place, explains Elizabeth Hadly, a palaeoecologist at Stanford University in California. It is also possible for mountains to have risen up from plains where there were once just, say, 10 species, she explains. The division created by the newly formed mountains could result in 20 unique species in the plains — 10 on either side of the mountains. Some of these species may ultimately find their way into the mountains to contribute to the increased diversity that is observed following tectonic activity. Indeed, adds Hadly, it is difficult to tell whether the evolution of new species happens in the plains, in the mountains, or both.

|

|

|

|

Post by nodstar on Sept 28, 2009 8:31:34 GMT 4

The Real Reason For Many UFO Abductions?[/SIZE] by Richard Sauder, keyholepublishing.com/Real%20Reason%20for%20Many%20UFO%20Abductions.htmlCopyright 2009, All Rights Reserved Many people, including me, have speculated about the Earth's possible crucial role as a giant, galactic library -- a huge repository of information stored in the DNA of the myriad species of biological life on this planet. This is not science fiction. Terrestrial, human scientists already know how to do this. Data stored in multiplying bacteria "A message encoded as artificial DNA can be stored within the genomes of multiplying bacteria and then accurately retrieved, US scientists have shown. Their concern that all current ways of storing information, from paper to electronic memory, can easily be lost or destroyed prompted them to devise a new type of memory - within living organisms. The scientists took the words of the song It's a Small World and translated it into a code based on the four "letters" of DNA. They then created artificial DNA strands recording different parts of the song. These DNA messages, each about 150 bases long, were inserted into bacteria such as E. coli and Deinococcus radiodurans. The latter is especially good at surviving extreme conditions. It can tolerate high temperatures, desiccation, ultraviolet light and ionising radiation doses 1000 times higher than would be fatal to humans. The beginning and end of each inserted message have special DNA tags devised by the scientists. These "sentinels" stop the bacteria from identifying the message as an invading a virus and destroying it. The magic of the sentinel is that it protects the information, so that even after a hundred bacterial generations (they) were able to retrieve the exact message." www.newscientist.com/article/dn3243Now think how much information can be stored in the DNA of all of the living organisms on this planet, including in the DNA of terrestrial humans. The entire biosphere, including the human race, may be an unimaginably huge, ancient, living, breathing, Galactic data archive. My extensive reading of the voluminous UFOlogy literature, as well as my own intuition, insights, visions, dreams and many conversations and communications with other researchers and thinkers over a period of many years lead me to conclude that this scenario is very likely true. This also may explain the well-documented obsession in the UFOlogical literature of extraterrestrial abductors with extracting human sperm and eggs from UFO abductees. It's not necessarily a sexual procedure, per se -- rather it's more akin to interplanetary reference librarians or industrial spies retrieving unique and encyclopedic data storage modules that contain voluminous information. It may be that terrestrial human DNA is a hot commercial commodity on the galactic market, for the information that it contains. Remember: information is power, and the information that we carry in our individual DNA may be very powerful, indeed. Imagine what would happen if our genetic blocks were undone -- what a total mind and reality blowing event that would be. No doubt, only a small fraction of humanity could handle that immensity. Imagine the vast potential we carry within us, all of us, encoded into the very structure of our DNA. Who knows what hidden, archived data the genetic and information scientists at Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore may be extracting from the human genome right now? For surely, they have long since understood that if terrestrial human scientists can store information in DNA and retrieve it, then others have been at the same game. But here's the bright side of the picture. Now that we know that information storage and retrieval in living DNA is scientific fact, we can play at that game too. It but remains for us to consciously retrieve the information stored from ages past in our own DNA, to recall what we carry within us and then to actually consciously become, for the first time in our lives, the empowered Galactic beings we have always potentially been! This is the next step in our evolution as a conscious, planetary species, moving out into the Galaxy with expanded awareness of who we are, and where we fit into the Grand Cosmic Mystery of Life.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 28, 2009 20:53:33 GMT 4

The Australian town that kicked the bottleDrinking fountains replace shop-bought mineral water in environmental initiativeThe Independent

Monday, 28 September 2009www.independent.co.uk/news/world/australasia/the-australian-town-that-kicked-the-bottle-1794273.htmlPlastic bottles were ceremoniously removed from shelves in the sleepy Australian town of Bundanoon at the weekend as a ban on commercially-bottled water – believed to be a world first – came into force.The ban, which is supported by local shopkeepers, means bottled water can no longer be bought in the town in the Southern Highlands, two hours from Sydney. Instead, reusable bottles have gone on sale, which can be refilled for free at new drinking fountains.Locals marched through the town on Saturday, led by a lone piper, to celebrate the start of the ban. John Dee, a campaign spokesman, said: "While our politicians grapple with the enormity of dealing with climate change, what Bundanoon shows is that at the very local level we can sometimes do things to bring about real and measurable change."The ban was triggered by a Sydney drinks company's plan to build a water extraction plant in the town. Huw Kingston, a cafe owner, said townsfolk were horrified by "the idea of them taking water here, trucking it to Sydney and bringing it back in bottles to be sold in shops at 300 times the tap price". Bottled water is widely viewed as an environmental menace, because of the energy consumed in producing and transporting it, and because most bottles end up in landfill sites. A New South Wales government study found the industry was responsible for releasing 60,000 tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2006. In recent years, dozens of local authorities in Britain and the US have stopped spending public money on bottled water. But Bundanoon, population 2,000, is believed to be the first community to ban it completely. Shelf space previously reserved for bottled water in the town's supermarket, off-licence, cafes and newsagent is now occupied by the reusable bottles. Filtered water fountains have been set up in the main street and at the local school; bottles can also be refilled in shops, for a small fee. Mr Dee said: "We're saying to people, you can save money and save the environment at the same time. The alternative doesn't have a sexy brand, doesn't have pictures of mountain streams on the front of it. It comes out of your tap." Only two people voted against the ban. One was concerned it would lead to more sugary drinks being consumed. The other was Geoff Parker, director of the Australasian Bottled Water Institute. This is great! Now we need to address the type of refillable bottles available. No BPA bottles, please.  It's a bit more difficult, but I've switched back to glass bottles. They're easier to clean - even canning jars are cool - and both are dishwasher safe. It's a bit more difficult, but I've switched back to glass bottles. They're easier to clean - even canning jars are cool - and both are dishwasher safe.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 28, 2009 21:56:25 GMT 4

Can one woman save Africa?Wangari Maathai saw trees being chopped down in her backyard in Kenya and dedicated her life to saving Africa's rainforests. Now it's time for the rest of the world to face some hard truths, the Nobel laureate tells Johann HariThe Independent

Monday, 28 September 2009www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/can-one-woman-save-africa-1794103.htmlWhen does planting a tree become a revolutionary act – and unleash an army of gunmen who want to shoot you dead? The answer to this question lies in the unlikely story of Wangari Maathai. She was born on the floor of a mud hut with no water or electricity in the middle of rural Kenya, in the place where human beings took their first steps. There was no money but there was at least lush green rainforest and cool, clear drinking water. But Maathai watched as the life-preserving landscape of her childhood was hacked down. The forests were felled, the soils dried up, and the rivers died, so a corrupt and distant clique could profit. She started a movement to begin to make the land green again – and in the process she went to prison, nearly died, toppled a dictator, transformed how African women saw themselves, and won a Nobel Prize. Now Maathai is travelling the world with a warning. As she told the United Nations climate summit last Tuesday, it is not just her beloved rainforest that is threatened now, but all rainforests. "As human beings, we are attacking our own life-support system," she says. "And if we carry on like this, we are digging our own grave."Her story begins with one particular tree in the heart of Africa. In 1940, Maathai became the third of six children born to illiterate peasant farmers. Her father worked as a "glorified slave" for the British settlers who occupied Kenya. He was forced to do what he was told on their farms, and forbidden – like all black people – from growing his own food and selling it. The nearby town of Nakuru was strictly segregated, with Africans banned from the "European areas." As a child, Maathai escaped into the natural landscape. She studied the forests – how they absorbed water and turned them into streams, and how they were filled with life. She would sit for hours under one particular fig tree, which her mother told her was sacred and life-giving and should never be damaged.

"That tree inspired awe. It was protected. It was the place of God. But in the Sixties, after I had gone far away, I went back to where I grew up," she says, "and I found God had been relocated to a little stone building called a church. The tree was no longer sacred. It had been cut down. I mourned for that tree. And I knew the trees had to live. They have to live so we can live." I. A Daughter of the Soil I am meeting Maathai in a busy hotel in London. She approaches me in the lobby – a tall, broad woman with a bright blue headdress and a slight limp – looking frazzled. "I have a flight in a few hours and I have packed nothing! Ah, you know how it is," she says. "Let's have coffee." As soon as we sit, she begins to talk about the trees, and a calm settles over her unlined 69-year-old face. "I am a daughter of the soil, and trees have been my life," she says. She begins to talk reverentially about how trees store carbon, regulate rainfall, hold soil in place, and provide food. "I can't live without the green trees, and nor can you. I'm humbled by the understanding that they could get along without me though! They sustain us, not the other way round. We don't really know where we came from, where we are going, and what the purpose of all this is. But we can look at the trees and the animals and each other, and realise we are part of a web we can't really control." She was only able to learn the hard science of the forests because her parents made a bold decision. At a time when girls were not often educated, her mother resolved to send her girl to school, and give her all the opportunities she had never had. The British settler her father worked for was furious: who was going to pick his pyrethrum? But her mother insisted – a rare and risky act of defiance. Maathai soon shot to the top of the class, and was offered a place at a Catholic boarding school run by Irish nuns. When she was 13, in her first year away at school, the rebellion against the British occupation broke out. The Mau Mau guerrilla fighters took on the British occupiers to drive them away, killing around 100 people. The British fought back with astonishing ferocity, killing around 100,000 Kenyans. "The Home Guards had a reputation for extreme cruelty and all manner of terror," she says. Her mother was forced out of her home at gunpoint and ordered to live in an "emergency village" – a glorified camp surrounded by trenches. Men were not allowed in. "My mother and father didn't see each other for seven years," she says. "I carried messages between them. That's how I ended up imprisoned for the first time." When she was 16, she was caught by British soldiers, and thrown into a detention camp. "The conditions were horrible – designed to break people's spirits and self-confidence and instill sufficient fear that they would abandon their struggle." It stank. She slept on the floor and wept. After two days, she was released. She adds: "I will never forget the misery in that camp. There is terrible trauma for everyone from those times." What does she think of the British historians who lyrically laud the British Empire, and say what happened in Kenya was merely a blip? "Well, that is the propaganda we all give to our subjects! They have to do that for them to support these terrible crimes." It was not only humans who were being cut down. Her forests began to be slashed by the British and replaced with vast commercial plantations growing tea for export. These plantations couldn't absorb and store water in the same way, so the groundwater levels fell to almost nothing, and the local streams dried up. After independence, Kenya's corrupt new ruling class continued the same policies, treating the forests as their private property to be pillaged. But Maathai was offered a way out, to a place where she could ignore all this. After scoring extremely highly on the national exams, she was granted a place at an American university. It would be fully paid-for by the US Government, as part of a policy introduced by John Kennedy. She was one of thousands of young Africans – including Barack Obama Sr – who became part of "the Kennedy airlift" to study there. At first, "I felt like I had landed on the moon." She remembers getting into her first elevator: "I thought I was going to be pulled apart!" She was shocked to see men and women dancing pressed up against each other and women with relative freedom. She stayed for four years, majoring in biology in Kansas, and "America changed me in every way. I saw the civil rights movement. It changed what I knew about how to be a citizen, how to be a woman, how to live. But I always knew I would go back." Her forests were calling. When she arrived back in Kenya, she soon became the first woman ever to get a PhD in East or Central Africa. She was a Professor by her mid-20s. But she was paid far less than men in the same position, and the entirely male student body at first refused to take lessons from her in anatomy. "But I showed them who was boss. A failing grade from me counted as much as from any man! That was a language they understood." She met a young Kenyan politician called Mwangi Maathai, and adored him. She became swept up in his campaign to gain a seat in parliament, and quickly married him – but it soon started to go bad. "When Mwangi won the election, I was so happy for him. I said – what are we going to do now to get jobs for all the people we promised help for? He just said – oh, that was the campaign." She pauses, disgusted still. "I couldn't believe what I was hearing. He didn't intend to do anything." She joined a group called the National Council of Women of Kenya, determined to give other people the opportunities she had been given. "Many of the girls I was at school with were back working in the fields and living in huts, and I wanted to help them," she says. When she went out into their areas, she saw the forests had been razed, and malnutrition was rife. She felt helpless and wondered what she could do. "Then it just came to me – why not plant trees? The trees would provide a supply of wood that would enable women to cook nutritious foods. They would also have wood for fencing, and fodder for cattle and goats. The trees would offer shade for humans and animals, protect watersheds and bind the soil, and if they were fruit trees, provide food. They would also heal the land by bringing back birds and small animals and regenerate the vitality of the earth."

She managed to persuade international aid organisations to pay women a very small sum – around 2p – for successfully planting each tree. At first, local men scoffed. What could women do? How could they make trees grow? What did this belong in our traditions? But women were soon organising themselves from village to village into independent committees. "We started by planting trees, but soon we were planting ideas! We were showing women could be an independent force. That they were strong." But a scandal was waiting that threatened to leave Maathai broken – and broke. II. Too strong Mwangi Maathai was jealous of his wife's intellect and expected her to be submissive and obedient. "He wanted me to fake failure and deny my God-given talents. But I wouldn't do it," she says. One morning, he announced he was divorcing her – and it became a national news story. Divorce was, at that time, a huge scandal – and the woman was always blamed. When the case came to open court, it was filled with journalists eager to report on Mwangi's charges that she was an adulterous witch who had caused his high blood pressure and refused to submit to his will. She was, he announced, "too educated, too strong, too successful, too stubborn, and too hard to control." The men in the courtroom cheered. "With every court proceeding, I felt stripped naked before my children, my family and friends. It was a cruel, cruel punishment," Maathai wrote in her autobiography, Unbowed. She adds: "I was being turned into a sacrificial lamb. Anybody who had a grudge against modern, educated and independent women was being given an opportunity to spit on me. I decided to hold my head high, put my shoulders back, and suffer with dignity: I would give every woman and girl reasons to be proud and never regret being educated, successful, and talented." The judge found in her husband's favour, saying she had been a disgrace as a wife and deserved nothing. A few days later, she criticised the judge in an interview for his sexism – and he ordered she be tossed into prison for contempt of court. "So not only had I lost my husband but I lost my freedom," she says. The other women prisoners were very kind to her: they let her sleep in the middle of the huddle, so she wouldn't be so cold. "Far from beating me down, I felt stronger. I knew I'd done nothing wrong." When she was released, she decided to run for parliament herself, to demand rights for women. She resigned from the university and announced her candidacy – only for another judge to declare she was ineligible to stand on the false grounds that she hadn't placed herself on the electoral register. The university – also under political pressure – refused to take her back. Suddenly, "I was 41 years old and I had no job, no money, and I was about to be evicted from my house. I didn't have enough money to feed my children. I remember them wanting chips, and I just couldn't afford it. You never forget the sound of your child crying with hunger." She rubs her head-dress softly and says: "I thought about my mother. She had survived everything life put at her. She had been kept apart from my father for seven years in an emergency village. She always survived." It was at this personal midnight that she returned to the small seeds she had begun to plant years before. She decided to urge women to plant whole forests. She wanted to see an entire new green belt across Kenya nurtured by women. A grant by the UN Development Programme and the Norwegian Government spurred it on, and she felt herself awakening again – along with the greening land. Then one day she read about a threat to some of the country's most precious trees. Daniel Arap Moi, the thuggish dictator of Kenya, decided to build over Uhuru Park, the only green space in the capital of Nairobi. He wanted to replace it with a giant skyscraper, some luxury apartments, and a huge golden statue of himself. So she decided to do something you weren't supposed to do in Moi's Kenya: protest. She led large marches to the park, and wrote to the project's international funders, asking if they would happily pay to concrete over Hyde Park or Central Park. "People said it would make no difference – that you can't make a dictator hear you, he's too strong," she says. "But I was in Japan a few years ago and I heard a story about a hummingbird. There's a huge fire in the forest and all the animals run out to escape. But the hummingbird stays, flying to and from a nearby river carrying water in its beak to put on the fire. The animals laugh and mock this little hummingbird. They say – the fire is so big, you can't do anything. But the hummingbird replies – I'm doing what I can. There is always something we can do. You can always carry a little water in your beak."But the initial reaction to her protests was frightening. She began to receive anonymous phone calls telling her should shut up or face death. Moi called her a "madwoman," and announced: "According to African traditions, women should respect their men! She has crossed the line!" When she carried on, she was charged with treason – a crime which carried the death penalty – and was slammed away in prison. She had arthritis, and she says: "In that cold, wet cell my joints ached so much I thought I would die." But she would not apologise, or give in. "What other people see as fearlessness is really persistence. Because I am focused on the solution, I don't see the danger. If you only look at the solution, you can defy anyone and appear strong and fearless." It was only after international protests began to gather – led by then-Senator Al Gore – that an embarrassed Moi had to let her go. She immediately started protesting again. After three years of campaigning against the developers and relentless death-threats, Moi finally relented. He dropped the project. The park was saved. A dictator defeated by a woman? Nothing like it had happened in Kenya before. It was the moment the Moi regime began to die. She says: "People began to think – if one little woman of no significance except her stubbornness can do this, surely the government can be changed." A great green wave of trees was starting to grow across the country: some 35 million have been planted by her Green Belt Movement. But her confrontation with Moi was not over. As a symbol of resistance, Maathai was contacted by a group of mothers whose sons had disappeared into the prison system, simply for democratically opposing the regime. They believed their sons were being tortured. They were frantic with fear and grief. Maathai realised she could not refuse them. She told them to gather up blanket and mattresses, because they were going to go to Central Nairobi, plant themselves in Moi's vision, and refuse to leave until he released their sons. On the first night, the police watched anxiously, unsure what to do. Hundreds of people gathered in solidarity. By the third day, there were thousands – and men started to publicly describe how they had been tortured by the police, and weep. "Nothing like it had happened in our country's history before," she says. But then the police swooped in with tear gas and batons. They beat the women hard, and Maathai hardest of all. She was carried away bleeding. When she had to sign her name at the police station, she dipped her finger in her own blood, pouring from a crack in her head, and scrawled her name with it. The next morning, all the women went back. Maathai was there too, in a neck brace and bandages, insisting she would not be intimidated. For a second time, Moi relented. There was a sense of shock in the country – the women had won against a Big Man again, using only peaceful political pressure. But there was a third confrontation coming. Moi announced he was going to raze most of the Karura Forest, one of the most precious green areas in Kenya. Again Maathai was there – this time facing down soldiers with machine guns, armed only with a small tree for her to plant. Again, she was beaten, and she nearly died. Again, she won in the end. Moi's rule was finally broken. Within a year, he was chased from office, and Kenya saw its first democratic elections in a generation. Maathai was elected to parliament in a landslide. III. Death of the rainforests? Are we in the rich world rendering these victories meaningless? As a scientist, Maathai is warning now that man-made global warming threatens to make the rainforests dry up and die, whatever she does in Kenya. She could save them from Moi – but can she save them from us?

"People don't realise how much they depend for their own survival on this ecosystem and how fragile it is," she says, almost pleading. "The world's forests are its lungs. Thick, healthy strands of indigenous trees absorb huge amounts of carbon dioxide and keep them out of the atmosphere. If the Congolese rainforests were entirely destroyed, for example, 135 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide would be released – equivalent to more than a decade of man-made emissions. So if we lose these forests, we lose the fight against climate change." The rainforests can be killed from two directions – by the saws of men like Moi, or the warming gases of people like us. That is why she has left the land she loves, armed with the Nobel Peace Prize she won in 2004, and travelled so far: to try to persuade us to let the forests live. "There are moments in history when humans have to raise their consciousness and see the world anew. This is one of those moments. We are being called to assist the earth in healing her wounds, and in the process we can heal our own. We can revive our sense of belonging to a larger community of life. We can see who we really are." When I tell her some people say environmentalism is a rich person's luxury without any relevance for the poor, she lets out a low scoff. "The exact opposite is the case! The people who are at greatest risk are poor. When the problems hit, it's them who are going to be hit worst. They have no money to adapt or flee. They still get their water from the rivers. Their agriculture is very dependent on rainfall. They will die first." If man-made global warming continues at the current rate, she says there will be "catastrophe" in Africa. "First of all there will be a fast spread of the Sahara desert. It is spreading now. So events like what is happening in Darfur will get much worse. There will be violent competition over shrinking arable land, grazing land and water points as the desert spreads and dries up the land. Second, there will be crop failure because of changing rainfall patterns, and we will get massive starvation. What happens then? As we all know, people don't sit down and wait to die. They migrate. They will try to come here to Europe." As she speaks, I remember the last time I saw the Congolese rainforest. Logging on a large scale had just begun, and the stumps of cut trees were visible everywhere, like stubble on a dry, cracking face. Maathai is a UN Goodwill Ambassador for this rainforest – and says saving it is an "urgent priority for us all. It covers 700,000 square miles. It is a quarter of all the tropical rainforest remaining on earth ... It affects weather patterns all over the world. It hasn't been cut a lot until now because the conflict there means it can't be accessed." But even the cutting down of trees in the Congo Basin that has already happened produced a 35 per cent drop in the amount of rain that falls in the Great Lakes Region of the United States in February. Does she believe there is a choice between encouraging development and saving the environment? "Not at all," she says quickly. "You don't reduce poverty in a vacuum. You reduce it in an environment. In Kenya, one of our biggest exports is coffee. Where do you grow coffee? You grow coffee in the land. To be able to grow coffee you need rain, you need special kinds of soil that are found on the hillsides, and that means you need to protect that land from soil erosion. You need to make sure they can hold the rain so that it flows as rivers and streams. You need forests to regulate the rainfall. You can't grow anything in a wrecked environment." In reality, "poverty is both a cause and a symptom of environmental degradation. They have to be dealt with together. When you're poor, you will take whatever you can to stay alive today, which degrades the environment, and makes you ever poorer. It's a matter of breaking the cycle. Paying people to plant trees was the best idea I had to break the cycle and it is working." But it is, she adds, not enough. For the forests – and a recognisable climate – to survive, there needs to be dramatic change on both sides. We in the West need to change our carbon emissions – and Africans, she says, need to change their culture, by rediscovering something that was smashed by colonialism. She says there is a "vacuum" at the heart of Africa – one that needs to be met by radically changing how the continent works. IV. The Taboo As she oversaw the mass planting of trees, Maathai steadily realised the ripping up and hacking down of the forests is only a symptom of a much-wider problem – one that was crippling Africa. "The disease remained. What made our leaders treat their own country like it was a colony, not something they were part of? It was the same disease that causes corruption and very bad leadership." There was something wrong in how African societies worked – something so deep and puzzling that she has just written a whole book trying to figure it out, called The Challenge For Africa. She touches on many problems, from global warming to unfair trade policies, but the most intriguing section is one that breaches a taboo about Africa – the fact that most Africans identify not with their country, but with their tribe. "Colonialism destroyed Africans' cultural and spiritual heritage," she says. "Any culture is accumulated knowledge and wisdom, built up over millennia. It tells you how to live in your environment, how to understand life. All our accumulated knowledge was wiped out in just a few years. It wasn't written down, so it died with our elders. Now it is lost forever." This had many effects: "Before, there was something deep in our culture that made us respect the environment. We didn't look at trees and see timber. We didn't look at elephants and see ivory. It was in our culture to let them be. That was wiped out." Part of her work is trying to restore that lost sense of respect for the ecosystem – one that has been proved essential by science. But this erasure of African culture also left another wound, one harder still to rectify. "It left us with a terrible lack of self-knowledge. Who are we? This is the most natural question for human beings. What group do I belong to? Where did I come from? We no longer had an answer." They were told to forget what came before. In Kenya when the British invaded, there were 42 different tribes – or "micro-nations", as she prefers to call them, because it removes the taint of "primitivism". These old identities were supposed to be abandoned for an identity that consisted of lines arbitrarily draw on a map by their European killers. "The modern African state is a superficial creation: a loose collection of ethnic communities brought together by the colonial powers," she says. "Most Africans didn't understand or relate to the nations created for them. They remained attached to their micronations." The result has been "a kind of political schizophrenia. Africans have been obscured from ourselves. It is like we have looked at ourselves through another person's mirror – and seen only cracked reflections and distorted images." They have been told to adopt identities like "Kenyan" that make no sense to them. "It is impossible to speak meaningfully of a South African, Congolese, Kenyan or Zambian culture," she explains. "There are only micronations. But we are still living in denial. We are denying who we are." The result is that when a leader comes to power, he doesn't try to govern on behalf of his people – and they don't expect him to. He delivers for his own tribe, at the expense of the others. "What they call 'the nation' is a veneer laid over a cultureless state – without values, identity, or character," she says. The mechanism of democratic accountability breaks down: the leader is not expected to serve his people, but only a small fraction of them. Elections consist of different tribes fighting to hijack the state to use in their own interests. The system of winner-takes-all democracy – where you need 50.5 per cent of the vote and get 100 per cent of the power – encourages this, and will never work in Africa, she says. Maathai believes there is a way out of this – but it is absolutely not to pretend tribes don't exist, or to urge people to simply overcome these identities. "We have been telling people to transcend their micronations for so long, and it hasn't happened. They are urged to shed the identity of their micronations and become citizens of the new modern state, even though no African really knows what the character of that modern state might be beyond a passport and an identity card. It doesn't work." The tribal violence in Kenya last year after the election was, she says, even more proof. She wants to find another route. Instead of a melting pot that pretends all identities will merge into one, she wants to create a salad bowl – one where every piece is different, but together they form a perfect whole. "Instead of all attempting the impossible task of being the same, we should learn to embrace our diversity," she writes in the book. "African children should be taught that the peoples of their country are different in some ways, but because of Africa's historical legacy, they need to work together ... The different micro-nations would be much more secure and likely to flourish if they accepted who they are and worked together. In my view, Africans have to re-embrace their micronational cultures, languages and values, and then bring the best of them to the table of the nation state." In addition to conventional parliaments, she says that in each African nation there should be assemblies bringing together all the different tribal groups, modelled on the United Nations. There, they could find common ground, and negotiate areas of disagreement. "It is the only way to heal a psyche wounded by denial of who they really are," she says. Every African should rediscover and feel comfortable in their tribal identity, and feel it is properly represented in the political structures of the state. Only then can they share and live together, she believes. That way, everyone will feel they have a stake in the state all the time – not just when one of their men has managed to seize the reins. She discovered this sense of calm when, in her forties, she rediscovered her Kikuyu roots. The Kikuyus had regarded the trees and Mount Kikuyu's glaciers as the closest thing they had to a sacred being, something worthy of respect. She too found value there, rather than in the dessicated texts left behind by the colonialists. "When they erased our culture, we were left with a vacuum, and it was filled with the values of the Bible – but that is not the coded values of our people." But isn't there a danger that you are romanticising past cultures and the equally-irrational beliefs that went with them? Weren't these cultures also committed to keeping women separate and subordinate? Isn't your great achievement to break with the traditional subordination of women? She nods. "Culture is a double-edged sword," she says. "It can be used to strike a blow for empowerment, or to keep down somebody who wants to be different. There are negative aspects to any culture. We should only retain what is good. We were taught for so long that what came before colonialism was all bad. It wasn't. We were told our attachment to the land was primitive and a block on progress. It wasn't. We had a ritual – ituika – through which leaders were accountable to their people and could be changed. And people took what they needed but didn't accumulate or destroy in the process. Those are values we need to rebuild in Africa." She suddenly leans forward and says: "That is the way we will save the rainforests, and prevent global warming!" She is going to follow this goal with the same feverish intensity that drove her from a mud-hut to the Nobel Prize, and enabled her to stand firm through beatings and imprisonments so she could knock down a dictator. Can will-power and a relentless focus on the solution pull us through the climate crisis as it pulled her through a tyranny? Before I can ask this, she stands up. "Now I must finish packing. My flight is so soon, and my clothes are all over the room!" In a whirl of bright green, she laughs and limps off through the lobby. She has a slightly pained gait, the result of too many nights sleeping on the floor of damp jail cells. She turns back and waves with a strange bend in her back – as if she is still weighed down, after all this time, by the ghost of that single felled fig tree she failed to save. "The Challenge For Africa" by Wangari Maathai is published by William Heinemann Limited. To order a copy at the special price of £18, including p&p, call Independent Books Direct on 08430 600 030

To support or donate to the Green Belt Movement, go to www.greenbeltmovement.org

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 28, 2009 22:31:30 GMT 4

By 2040 you will be able to upload your brain......or at least that's what Ray Kurzweil thinks. He has spent his life inventing machines that help people, from the blind to dyslexics. Now, he believes we're on the brink of a new age – the 'singularity' – when mind-boggling technology will allow us to email each other toast, run as fast as Usain Bolt (for 15 minutes) – and even live forever. Is there sense to his science – or is the man who reasons that one day he'll bring his dad back from the grave just a mad professor peddling a nightmare vision of the future?The Independent

Sunday, 27 September 2009www.independent.co.uk/news/science/by-2040-you-will-be-able-to-upload-your-brain-1792555.htmlShould, by some terrible misfortune, Ray Kurzweil shuffle off his mortal coil tomorrow, the obituaries would record an inventor of rare and visionary talent. In 1976, he created the first machine capable of reading books to the blind, and less than a decade later he built the K250: the first music synthesizer to nigh-on perfectly duplicate the sound of a grand piano. His Kurzweil 3000 educational software, which helps students with learning difficulties such as dyslexia and attention deficit disorder, is likewise typical of an innovator who has made his name by combining restless imagination with technological ingenuity and a commendable sense of social responsibility. However, these past accomplishments, as impressive as they are, would tell only half the Kurzweil story. The rest of his biography – the essence of his very existence, he would contend – belongs to the future. Following the publication of his 2005 book, The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, Kurzweil has become known, above all, as a technology speculator whose predictions have polarised opinion – from stone-cold scepticism and splenetic disagreement to dedicated hero worship and admiration. It's not just that he boldly envisions a tomorrow's world where, for example, tiny robots will reverse the effects of pollution, artificial intelligence will far outstrip (and supplement) biological human intelligence, and humankind "will be able to live indefinitely without ageing". No, the real reason Kurzweil has become such a magnet for blogospheric debate, and a tech-celebrity, is that he's convinced those future predictions – and many more just as stunning – are imminent occurrences. They will all, he steadfastly maintains, happen before the middle of the 21st century. Which means, regarding the earlier allusion to his mortal coil, that he doesn't plan to do any shuffling any time soon. Ray Kurzweil, 61, sincerely believes that his own immortality is a realistic proposition ... and just as strongly contends that, using a combination of grave-site DNA and future technologies, he will be able to reclaim his father, Fredric Kurzweil (the victim of a fatal heart attack in 1970), from death. Just when will this ultimate life-affirming feat be possible? In Kurzweil's estimation, we will be able to upload the human brain to a computer, capturing "a person's entire personality, memory, skills and history", by the end of the 2030s; humans and non-biological machines will then merge so effectively that the differences between them will no longer matter; and, after that, human intelligence, transformed for the better, will start to expand outward into the universe, around about 2045. With this last prediction, Kurzweil is referring not to any recognisable type of space travel, but to a kind of space infusion. "Intelligence," he writes, "will begin to saturate the matter and energy in its midst [and] spread out from its origin on Earth." It's as well to mention at this point that, in 2005, Mikhail Gorbachev personally congratulated Kurzweil for foreseeing the pivotal role of communications technology in the collapse of the Soviet Union, and that Microsoft chairman Bill Gates calls him "the best person I know at predicting the future of artificial intelligence". A man of lesser accomplishments, touting the same head-spinning claims, would impress few beyond an inner circle of sci-fi obsessives, but Kurzweil – honoured as an inventor by US presidents Lyndon B Johnson and Bill Clinton – has rightfully earned himself a stockpile of credibility. In person, chewing pensively on a banana, the softly spoken, slightly built Kurzweil looks chipper for his 61 years, and wears an elegantly tailored suit. A father of two, he resides in the Boston suburbs with his psychologist wife, Sonya, but has flown into Los Angeles for a private screening of Transcendent Man, the upcoming documentary that examines his life and theories over a suitably cosmic score by Philip Glass. "People don't really get their intellectual arms around the changes that are happening," he says, perched lightly on the edge of a large armchair, his overall sheen of wellbeing perhaps a shade more encouraging than you'd expect from a man of his age. "The issue is not just [that] something amazing is going to happen in 2045," he says. "There's something remarkable going on right now." To understand exactly what he means, and why he thinks that his predictions bear up to hard scrutiny, it's necessary to return to the title of the above-mentioned book, and the grand idea on which it's based: "the singularity". Borrowed from black-hole physics, in which the singularity is taken to signify what is unknowable, the term has been applied to technology to suggest that we haven't really got a clue what's going to happen once machines are vastly more "intelligent" than humans. The singularity, writes Kurzweil, is "a future period during which the pace of technological change will be so rapid, its impact so deep, that human life will be irreversibly transformed". He is not unique in his adoption of the idea – the information theorist John von Neumann hinted at it in the 1950s; retired maths professor and sci-fi author Vernor Vinge has been exploring it at length since the early 1980s – but Kurzweil's version is currently the most popular "singularitarian" text. "I didn't come to these ideas because I had certain conclusions and worked backwards," he explains. "In fact, I didn't start looking for them at all. I was looking for a way to time my inventions and technology projects as I realised timing was the critical factor to success. And I made this discovery that if you measure certain underlying properties of information technology, it follows exquisitely predictable trajectories." For Kurzweil, the crux of the singularity is that the pace of technology is increasing at a super-fast, exponential rate. What's more, there's also "exponential growth in the rate ' of exponential growth". It is this understanding that gives him the confidence to believe that technology – through an explosion of progress in genetics, nanotechnology and robotics – will soon surpass the limits of his imagination. It is also why, in addition to bananas and the odd beneficial glass of red wine, he follows a regime of around 200 vitamin pills daily: not so much a diet as an attempt to "aggressively re-programme" his biochemistry. He claims that tests have shown he aged only two biological years over the course of 16 actual vitamin-popping years. He also says that, thanks to the regime, he has effectively cured himself of Type 2 diabetes. Not even open-heart surgery, which he underwent last year, and from which he made a rapid recovery ("a few hours later I was in the next room, and sent an email") could dent his convictions. On the contrary, he thinks that the brevity of his convalescence is proof positive that the pills are working. If he slows down the ageing process, he reckons, he'll be around long enough to witness the arrival of technology that will prolong his life... forever. Kurzweil was raised in Queens, New York, where two youthful obsessions – electronics and music – would lead to a guest appearance on the 1960s TV quiz show I've Got a Secret, on which (aged 17) he showcased his first major invention: a home-made computer that could compose tunes. Five years later came the death (in 1970, when Ray was 22) of his father, Fredric, a struggling composer and conductor who, Kurzweil believes, never really got his due. "I'm painfully aware of the limitations he had, which were not his fault," he says. "In that generation, information about health was not very available, and we didn't have [today's] resources for creating music. Now, a kid in a dorm room can create a whole orchestral composition on a synthesizer." The tragedy of that loss – and the fact that the means to repair a congenital heart defect were available to him, but not his father – is clearly an intense motivation for Kurzweil. Sometime soon, he believes, he will once again be able to converse with his father, such is the potential of the scientific advances he believes will ultimately pave the way to the singularity. Not everyone, though, concurs with his appraisal of technological progress, and his belief in the imminence of immortality. Memorably, in the Transcendent Man documentary, Kevin Kelly, founding editor of future-thinking magazine Wired, labels Kurzweil a "deluded dreamer" who is "performing the services of a prophet". In reacting to that assessment, Kurzweil's habitually mellow tone of voice takes on a hint – albeit mild – of umbrage. "It's interesting that [Kelly] says my views are 'hard-wired', when I actually think his views are hard-wired," he says. "He's a linear thinker, and linear thinking is hard-wired in our brains: it worked very well 1,000 years ago. Some people really are resistant to accepting this exponential perspective, and they're very smart people. You show them the data, and yes, they follow it, but they just cannot get past it. Other people accept it readily." Whereas Kelly differs from Kurzweil on the grounds of interpretation and tone, other voices of dispute are rooted in a deep-seated fear of technological calamity. "The form of opposition from fundamentalist humanists, and fundamentalist naturalists – that we should make no change to nature [or] to human beings – is directly contrary to the nature of human beings, because we are the species that goes beyond our limitations," counters Kurzweil. "And I think that's quite a destructive school of thought – you can show that hundreds of thousands of kids went blind in Africa due to the opposition to [genetically engineered] golden rice. The opposition to genetically modified organisms is just a blanket, reflexive opposition to the idea of changing nature. Nature, and the natural human condition, generates tremendous suffering. We have the means to overcome that, and we should deploy it." To those opponents who detect a thick strain of techno-evangelism in Kurzweil's basically optimistic interpretation of the singularity, he reacts with self-parody: there's a tongue-in-cheek photo in The Singularity is Near of the author wearing a sandwich board bearing the book's title, and he insists he was never "searching for an alternative to customary faith". At the same time, he says humankind's inevitable move towards non-biological intelligence is "an essentially spiritual undertaking". Whether or not he attracts a significant following of dedicated believers in search of deliverance, ecstasy or any variation thereof (some commentators have called the singularity "the rapture for geeks"), Kurzweil has undoubtedly positioned himself at the heart of a growing singularity industry. He is a director of the non-profit Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence, "the only organisation that exists for the expressed purpose of achieving the potential of smarter-than-human intelligence safer and sooner"; there's a second film awaiting release (part fiction, part documentary, co-produced by Kurzweil), also based on The Singularity is Near; and in addition to his theoretical books, he has co-authored a series of health titles, including Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever and Fantastic Voyage: Live Long Enough to Live Forever. The secret of immortality, he wants you to know, is available in book form. Those who have lent Kurzweil their support include space-travel pioneer Peter Diamandis, chairman of the X-Prize Foundation; videogame designer (and creator of Spore and SimCity) Will Wright; and Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist George Smoot. All three can be found on the faculty and adviser list of the recently founded Singularity University (Silicon Valley), of which Kurzweil is chancellor and trustee. If the pace of technology continues to accelerate, as Kurzweil predicts, it seems likely that discussion of the singularity will see an exponential growth of its own. Few would dispute that it's one of the 21st century's most compelling ideas, because it connects issues that intensely polarise people (God, the energy crisis, genetic engineering) with sci-fi concepts that stir the imagination (artificial intelligence, immersive virtual reality, molecular engineering). Thanks largely to Kurzweil and the singularity, scenarios once viewed as diverting entertainment are being reappraised with a new seriousness. The line between fanciful thinker and credible, scientific analyst is becoming blurred: what once would have been relegated to the realms of sci-fi is now gaining factual currency. "People can wax philosophically," says Kurzweil. "It's very abstract – whether it's a good thing to overcome death or not – but when it comes to some new methodology that's a better treatment for cancer, there's no controversy. Nobody's picketing doctors who put computers inside people's brains for Parkinson's: it's not considered controversial." Might that change as more people become aware of the singularity and the pace of technological change? "People can argue about it," says Kurzweil, relaxed as ever within his aura of certainty. "But when it comes down to accepting each step along the way, it's done really without much debate." 'Transcendent Man' (transcendentman.com) screens at Sheffield Doc/Fest (0114 276 5141, sheffdocfest.com), running in association with 'The Independent', from 4-8 November The greatest thing since sliced bread? Ray Kurzweil's guide to incredible future technologies — and when he thinks they're likely to arrive... 1 - Reconnaissance dust"These so-called 'smart dust' – tiny devices that are almost invisible but contain sensors, computers and communication capabilities – are already being experimented with. Practical use of these devices is likely within 10 to 15 years" 2 - Nano assemblers"Basically, these are three-dimensional printers that can create a physical object from an information file and inexpensive input materials. So we could email a blouse or a toaster or even the toast. There is already an industry of three-dimensional printers, and the resolution of the devices that can be created is getting finer and finer. The nano assembler would assemble devices from molecules and molecular fragments, and is about 20 years away" 3 - Respirocytes"A respirocyte is a nanobot (a blood cell-sized device) that is designed to replace our biological red blood cells but is 1,000 times more capable. If you replaced a portion of your biological red blood cells with these robotic versions you could do an Olympic sprint for 15 minutes without taking a breath, or sit at the bottom of a swimming pool for four hours. These are about 20 years away" 4 - Foglets"Foglets are a form of nanobots that can reassemble themselves into a wide variety of objects in the real world, essentially bringing the rapid morphing qualities of virtual reality to real reality. Nanobots that can perform useful therapeutic functions in our bodies, essentially keeping us healthy from inside, are only about 20 years away. Foglets are more advanced and are probably 30 to 40 years away" 5 - Blue goo"The concern with full-scale nanotechnology and nanobots is that if they had the capability to replicate in a natural environment (as bacteria and other pathogens do), they could destroy humanity or even all of the biomass. This is called the grey goo concern. When that becomes feasible we will need a nanotechnology immune system. The nanobots that would be protecting us from harmful self-replicating nanobots are called blue goo (blue as in police). This scenario is 20 to 30 years away"

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 28, 2009 22:54:40 GMT 4

Australia 'uranium' dust concernsBBC News

updated at 04:59 GMT, Monday, 28 September 2009 05:59 UKnews.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/8277924.stmA cold front combined with strong winds whipped up topsoil from the dried-out Lake Eyre basin and swept across New South Wales spreading about 600km along the east coastEnvironmentalists have raised concerns that another giant dust storm blowing its way across eastern Australia may contain radioactive particles. It is argued that sediment whipped up from Australia's centre may be laced with material from a uranium mine. Scientists have played down concerns, saying there is little to worry about. Last Wednesday Sydney and Brisbane bore witness to their biggest dust storm in 70 years. Both were shrouded in red dust blown in from the desert outback. The massive clouds of dust that choked heavily populated parts of Australia have caused problems for people with asthma, as well as those with heart and lung conditions. But some environmental campaigners believe that the dry, metallic-tasting sediment could threaten the health of millions of other Australians. David Bradbury, a renowned filmmaker and activist, claims the haze that engulfed some of the country's biggest cities in the past week contains radioactive grains - or tailings - carried on gale force winds from a mine in the South Australian desert. "Given the dust storms... which [the] news said originated from Woomera, and which is right next door to the Olympic Dam mine at Roxby Downs, these [storms] could blow those tailings across the face of Australia," Mr Bradbury asserted. Mining companies have stressed that dust levels are carefully monitored, while the health concerns have been dismissed by a senior environmental toxicologist. Barry Noller from the University of Queensland says that many of the particles from mines in the outback are simply too heavy to be carried by the wind over long distances. "In a big dust storm, the dust is not going to come from one isolated site, it is going to be mixed in with dust from a [wide] area and diluted considerably," Mr Noller said. The latest murky haze that spread over parts of Queensland at the weekend is dissipating and weather forecasters say it should soon start to move out to sea.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 28, 2009 23:11:17 GMT 4

WHOA...Sometimes I wonder about the Wellness Trust and the projects it funds. This is one of the reasons why:Key to subliminal messaging: keep it negative, study suggestsCourtesy Wellcome Trust

and World Science staff

Sept. 28, 2009www.world-science.net/othernews/090928_subliminalSubliminal messaging is most effective when the message being conveyed is negative, according to new research. Subliminal images – that is, images shown so briefly that a viewer doesn’t consciously notice them – have long been the subject of controversy, particularly in the advertising field. Studies have hinted that people can unconsciously pick up on subliminal information intended to provoke an emotional response, but limitations in the designs of the studies have meant that the conclusions weren’t considered definitive. A new study by Nilli Lavie of University College London and colleagues, indicates that people can process emotional information from subliminal images and that information of “negative value” is better detected than information of “positive value.” Lavie’s team showed 50 participants words on a computer screen. Each word appeared on-screen for only a fraction of second – at times only a fiftieth, much too fast for viewers to consciously read. The words were either positive, such as “cheerful,” “flower” and “peace”; negative, such as “agony,” “despair” and “murder”; or neutral, such as “box,” “ear” or “kettle.” After each word, participants were asked to decide whether the word was neutral, positive or negative, even if they had to just “guess.” Participants were found to answer most accurately when responding to negative words – even when they believed they were merely guessing. “Clearly, there are evolutionary advantages to responding rapidly to emotional information,” said Lavie. “We can’t wait for our consciousness to kick in if we see someone running towards us with a knife or if we drive under rainy or foggy weather conditions and see a sign warning ‘danger.’” Lavie said the research may have implications for the use of subliminal marketing to convey messages, both for advertising and public service announcements such as safety campaigns. “Negative words may have more of a rapid impact,” she explained. “‘Kill your speed’ should be more noticeable than ‘Slow down’. More controversially, highlighting a competitor’s negative qualities may work on a subliminal level much more effectively than shouting about your own selling points.” The findings were published Sept. 27 in the research journal Emotion. I certainly do not believe that we've anything to gain from a "negative" subliminal message or ad campaign other than an increase in the "Theory of Negative Relativity". Perhaps we should embrace our understanding and application of how positive messages pull forth a POSITIVE EMOTIONAL RESPONSE. And it need NOT be subliminal. That would be an incredible "evolutionary advantage", since it would allow for the continuance of evolution.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 28, 2009 23:34:15 GMT 4

HIV’s Ancestors May Have Plagued First MammalsScienceDaily

Sep. 28, 2009www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/09/090927145354.htmThe retroviruses which gave rise to HIV have been battling it out with mammal immune systems since mammals first evolved around 100 million years ago – about 85 million years earlier than previously thought, scientists now believe. The remains of an ancient HIV-like virus have been discovered in the genome of the two-toed sloth [Choloepus hoffmanni] by a team led by Oxford University scientists who publish a report of their research in this week’s Science. 'Finding the fossilised remains of such a virus in this sloth is an amazing stroke of luck,’ said Dr Aris Katzourakis from Oxford’s Department of Zoology and the Institute for Emergent Infections, James Martin 21st Century School. ‘Because this sloth is so geographically and genetically isolated its genome gives us a window into the ancient past of mammals, their immune systems, and the types of viruses they had to contend with.’ The researchers found evidence of ‘foamy viruses’, a particular kind of retrovirus that resembles the complex lentiviruses, such as HIV and simian retroviruses (SIVs) – as opposed to simple retroviruses that are found throughout the genomic fossil record. ‘In previous work we had found evidence for similar viruses in the genomes of rabbits and lemurs but this new research suggests that the ancestors of complex retroviruses, such as HIV, may have been with us from the very beginnings of mammal evolution,’ said Dr Aris Katzourakis. Understanding the historical conflict between complex viruses and mammal immune systems could lead to new approaches to combating existing retroviruses, such as HIV. It can also help scientists to decide which viruses that cross species are likely to cause dangerous pandemics – such as swine flu (H1N1) – and which, like bird flu (H5N1) and foamy viruses, cross this species barrier but then never cause pandemics in new mammal populations. Adapted from materials provided by University Of Oxford.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 28, 2009 23:45:31 GMT 4

Reviewers prefer positive findings Journals may be less likely to publish equivocal studiesScienceNews

October 10th, 2009; Vol.176 #8 (p. 9)www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/47826/title/Reviewers_prefer_positive_findingsVANCOUVER, Canada — Peer reviewers for biomedical journals preferentially rate manuscripts with positive health outcomes as better, a new study reports. The findings caused a buzz when presented September 11 at the International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication. If positive trials are preferentially published, explains Seth Leopold of the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, doctors will get a skewed impression of a therapy’s value: “Novel treatments will appear more effective than they actually are.”To test whether journals give negative or equivocal findings short shrift—despite pledging not to—Leopold’s team asked more than 200 trained reviewers at two orthopedic journals to rate whether manuscripts were worthy of publication. The team included a bogus manuscript in two forms. Data in the first showed better prevention of infection by one of two antibiotic regimens. In the second version, neither treatment outperformed the other but the results still would have affected patient care. The papers were identical, except for the outcomes. Among the 55 reviewers at one journal who were asked to evaluate the positive-outcome manuscript, 98 percent recommended that the journal publish it. Only 71 percent of another 55 reviewers from the journal who got the no-difference paper rated it ready for prime time. A similar, though not statistically significant, trend emerged at the second journal. Readers at both journals gave the positive paper’s method section higher ratings, even though the other paper had identical methods. And readers of the positive paper were less likely to spot intentionally included mistakes, Leopold reported. NOTE: To find out more, read a longer Science & the Public blog entry by Janet Raloff on this topic posted on September 11 and available here.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 29, 2009 0:22:12 GMT 4

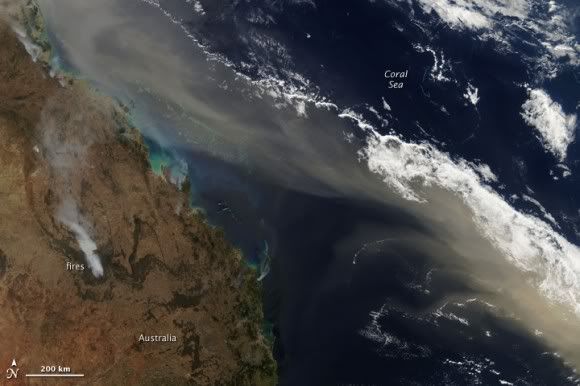

Noddie posted pictures and articles referencing the recent Australian Red Dust storms here and here.

Here is a related article and pictures taken by NASA's MODIS from space:From Space: Huge River of Dust Over AustraliaUniverse Today

September 25th, 2009www.universetoday.com/2009/09/25/from-space-huge-river-of-dust-over-australia/#more-41487A river of dust over Eastern Australia on Sept. 24, 2009. NASA image courtesy Jeff Schmaltz, MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption by Holli Riebeek.This isn't a special effect image from a new catastrophe movie; it is an actual satellite image of the dust storm sweeping over and around eastern Australia, heading across the Tasman Sea toward New Zealand. A dense wall of dust descended upon Sydney on Sept. 23, creating an apocalyptic scene ( see these images from Boston Globe's Big Picture) and the river of dust continues unabated across water. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this image of the storm on September 24, at 11:10 a.m., New Zealand time (23:10 UTC on September 23). The distance between the far northern edge of the plume and the southern edge is about 3,450 kilometers (2,700 miles), roughly equivalent to the distance between New York City and Los Angeles. Below, see how the storm progressed across the Sea later in the day. Dust storm over Australia during the afternoon of Sept. 24, 2009. NASA image courtesy Jeff Schmaltz, MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. By the early afternoon of September 24, 2009, when the same satellite acquired this image, the thick dust that had covered the eastern shore of Australia previouly, stretched in a long plume from northern Queensland to New Zealand. This image shows the northern portion of the plume off the coast of Queenland. The tan dust is densely concentrated in a compact plume that mirrors the coastline. The gem-like blue-green Great Barrier Reef is visible beneath the plume near the top of the image where the tan dust mingles with gray-brown smoke from wildfires.

|

|

|

|

Post by towhom on Sept 29, 2009 0:37:01 GMT 4

Third and Final Flyby of Mercury for MESSENGER Next WeekUniverse Today

September 24th, 2009www.universetoday.com/2009/09/24/third-and-final-flyby-of-mercury-for-messenger-next-week/Next week, on September 29, 2009 the MESSENGER spacecraft will fly by Mercury for the third and final time, looking at areas not seen before in the two previous passes. The spacecraft will pass 141.7 miles above the planet’s rocky surface, receiving an a final gravity assist that will enable it to enter orbit about Mercury in 2011. With more than 90 percent of the planet’s surface already imaged, the team will turn its instruments during this flyby to specific features to uncover more information about the planet closest to the Sun. Determining the composition of Mercury's surface is a major goal of the orbital phase of the mission. "This flyby will be our last close look at the equatorial regions of Mercury, and it is our final planetary gravity assist, so it is important for the entire encounter to be executed as planned," said Sean Solomon, principal investigator at the Carnegie Institution in Washington. "As enticing as these flybys have been for discovering some of Mercury's secrets, they are the hors d'oeuvres to the mission's main course — observing Mercury from orbit for an entire year."  As the spacecraft approaches Mercury, cameras will photograph previously unseen terrain. As the spacecraft departs, it will take high-resolution images of the southern hemisphere. Scientists expect the spacecraft's imaging system to take more than 1,500 pictures. Those images will be used to create a mosaic to complement the high resolution, northern-hemisphere mosaic obtained during the second Mercury flyby. The first flyby took the spacecraft over the eastern hemisphere in January 2008, and the second flyby took it over western side in October 2008. "We are going to collect high resolution, color images of scientifically interesting targets that we identified from the second flyby," said Ralph McNutt, a project scientist at APL. "The spectrometer also will make measurements of those targets at the same time." The spacecraft may observe how the planet interacts with conditions in interplanetary space as a result of activity on the sun. During this encounter, high spectral- and high spatial-resolution measurements will be taken again of Mercury's tenuous atmosphere and tail. "Scans of the planet's comet-like tail will provide important clues regarding the processes that maintain the atmosphere and tail," said Noam Izenberg, the instrument's scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL, in Laurel, Maryland. " The Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer will give us a snapshot of how the distribution of sodium and calcium vary with solar and planetary conditions. In addition, we will target the north and south polar regions for detailed observations and look for several new atmospheric constituents." For a detailed look at the MESSENGER flyby, see the MESSENGER website; additionally, Emily Lakdawalla at the Planetary Society has posted a detailed overview here.

|

|

|

|

Post by galaxygirl on Oct 3, 2009 16:13:30 GMT 4

|

|

|

|

Post by Eagles Disobey on Oct 3, 2009 20:00:07 GMT 4

I showed Dan the recent find of "Ardi" while he was just settling in to his new "digs" in the hospital. And by the way, they have already upgraded him to GOOD condition! ;D YEAH DANNY! news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20091001/ap_on_sc/us_sci_before_lucy_7He looked at the report and said it is marvelous! Then he stopped and something came out of him that is an "ONLY DAN" moment! ;D He looked and the names and said, "I wonder if anyone has noticed the nicknames? Lucy and Ardi? Or maybe it was planned? (laughed ;D ) Ardi is a Hebrew name for "Wild Ox." Luci means "Light." The winged Ox is the symbol of St. Luke, no? Luke means "bright, white" and when one looks at an anagram of ardilucy we can see "LUCID RAY." How unique! And if that isn't cool enough, think of the Arabian poem about pride and true glory. How sweet!"[/b][/color] Well I looked it up and by G-d it's there! ;D www.sacred-texts.com/isl/arp/arp069.htmON

THE INCOMPATIBILITY OF PRIDE

AND TRUE GLORY.

BY ABU ALOLA.

THINK not, Abdallah, Pride and Fame

Can ever travel hand in hand;

With breast opposed, and adverse aim,

On the same narrow path they stand.

Thus Youth and Age together meet,

And Life's divided moments share:

This can't advance till that retreat;

What's here increased, is lessened there.

And thus the falling shades of Night

Still struggle with the lucid ray,

And ere they stretch their gloomy flight,

Must win the lengthened space from Day. WOW! ;D Dan's "coming back!" ;D Stan |

|

|

|

Post by Eagles Disobey on Oct 3, 2009 20:31:00 GMT 4

Mountains may be cradles of evolution [/size] Natural News www.nature.com/news/2009/090925/full/news.2009.952.html?s=news_rss2009-09-27  Growing mountains may give rise to new species — and not simply provide a refuge to species whose traditional habitats have been lost, US scientists suggest. "The major times of [species] diversification directly coincide with times of large tectonic events," says Catherine Badgley, a palaeontologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who presented the findings this week at the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Bristol, UK. Mountainous regions are known to harbour higher levels of species richness than other areas. The reason, ecologists argue, is because mountains offer many different habitats in a relatively small geographical area. For example, whereas ten square kilometres of plains offer just one habitat, the same area of mountain landscape can provide sloping meadows, peaks and cliffs, all with different temperatures, rainfall and vegetation. The long-standing view among ecologists has been that mountainous areas act as refuges for species that have been driven out of their normal habitat by difficult environmental conditions. A typical example could be a species dwelling in plains near the base of mountains — a change in conditions on the plains might mean that mountain areas begin to suit the needs of the species better, causing it to migrate. "Mountains have always been considered the places for species to make their last stands because they offer such diverse terrain," notes Russell Graham, a palaeoecologist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. Curious about the mechanisms responsible for making mountains so rich in diversity, Badgley and her collaborator John Finarelli, also at the University of Michigan, studied mountain and lowland speciation rates and species richness using the fossil record of the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains in North America. The fossils they inspected date to the Miocene period, which began around 23 million years ago and ended about 5 million years ago. They found that there were bursts of speciation that took place only in the mountains during times of tectonic activity. During all other times, they discovered that speciation rates in the two regions were moderate and similar. Isolating incident Although the highly varied terrain of mountains helps to explain why so many different species can live there, the question of where the species richness actually comes from has never been addressed, explains Badgely. She and Finarelli now propose that as mountains are lifted up by the tectonic processes of the Earth's crust, mountain-dwelling species become isolated from other members of the same species living at lower altitudes. This isolation ultimately leads to the two groups breaking apart to form individual species. "We had never thought of mountains as the birthplaces of species before," says Graham. However, mountains might not be the only areas where speciation is taking place, explains Elizabeth Hadly, a palaeoecologist at Stanford University in California. It is also possible for mountains to have risen up from plains where there were once just, say, 10 species, she explains. The division created by the newly formed mountains could result in 20 unique species in the plains — 10 on either side of the mountains. Some of these species may ultimately find their way into the mountains to contribute to the increased diversity that is observed following tectonic activity. Indeed, adds Hadly, it is difficult to tell whether the evolution of new species happens in the plains, in the mountains, or both. [/quote] And why was Dan asking about the Alps? ;D I've asked Dan to just come out with it, about evolution, and plainly state his stance, but he stated that his overall "stance" is something he has to hold onto until he writes his "theory" what we have been calling his "magnum opus." Morbid as it is, I asked him if it was plainly written down "just in case" anything happens? He said "yes." Stan |

|

It's a bit more difficult, but I've switched back to glass bottles. They're easier to clean - even canning jars are cool - and both are dishwasher safe.

It's a bit more difficult, but I've switched back to glass bottles. They're easier to clean - even canning jars are cool - and both are dishwasher safe.